|

Lincoln Street Fire, 1893

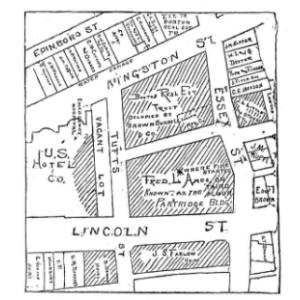

One of the largest fires in Boston history took place on March 10, 1893. A small fire in a restroom of a toy wholesaler spread to a storage room full of fireworks, which exploded, and caused a huge conflagration. The fire took place at Essex and Lincoln Streets in what was known as the Ames Building. At least five people were killed, with victims trapped at different levels of the six-story structure. A man deliberately jumped from a window and entangled himself in a web of telegraph wires, and then fell another forty feet and was caught by firefighters in a safety net.

Young women were trapped in the higher stories of the building, and chose to jump from windows to avoid being burned to death. A newspaper account stated, "The pitiful cries of girls imprisoned in the upper stories stirred the pulse of every spectator, but it was impossible to render aid." So many people were jumping from the building at the same time, that firefighters did not have enough nets or men to catch them. It is a miracle that more people were not killed in the disaster. The tragedy is similar in nature to the 1911 Triangle Waist-Coat Factory fire in New York City. The Triangle fire was many times more horrific, with huddled and burning groups of women falling from the top story of the building as the windows shattered from the intense heat.

The March 16, 1893 issue of the Meriden Weekly Republican describes how one brave firefighter saved many people:

"When I reached the second story [of the Ames building] and entered the room on the Lincoln street side the sight was most pitiful. Men, women and girls, frenzied with fear, were struggling to reach the windows to throw themselves into the street. Taking one at a time I lowered them by the hands as far as I could and then dropping them into the nets spread for them below, at the same time fighting the mad crowd back from the windows. The cries of frightened creatures were heart rendering, while the men seemed to lose all presence of mind and fought like demons. I think I succeeded in lowering some 25 or 30. I should say that there must have been at least 30 who who never came out of the building alive, although it is impossible for any one to estimate the loss of life in the building."

While the firefighters were trying to save people in the Ames Building, bursting fireworks and other explosions shattered the floors and sent missiles into the street below. A wall on Tufts Street collapsed, with debris falling into the street and injuring several people. South Station is nearby, and thousands of people clogged the neighboring streets to catch a glimpse of the great fire. An area bounded by Kingston, Essex, Lincoln and Beach Streets was flattened or sustained major damaged. The fire started in a third floor restroom, and may have been caused by an improperly discarded cigarette. An article in The Daily Times (Wilkes-Barre PA) of March 11, 1893 describes the destruction:

"The fire which broke out about 4 o’clock was caused by an explosion of fireworks in the factory of Horace Partridge, in a building owned by F.L. Ames, at the corner of Lincoln and Essex Streets. Several explosions followed the first and the flames spread with alarmingly rapidity.

The United States hotel, an historic structure, was burned to the ground. The old New Colony passenger depot, now used by express companies, was soon in flames, and the fire was eating rapidly to the north and west toward Washington street.

It got beyond the control of the fire department in a very few minutes and telegrams were sent to all the neighboring cities for help.

Engines came from Worcester, Framingham, Newton, Waltham, Quincy, Hyde Park, Cambridge, Chelsea, Lynn, Malden, Newburyport, Salem, Haverhill, Lawrence, Lowell and Fitchburg, and all went to work to prevent the flames from devastating Washington and Devonshire streets and Harrison avenue.

The fire assumed such dimensions that Governor Russell ordered out the First and Ninth regiments of the National Guard to preserve order and establish fire lines.

Scores of burned and injured people were taken into the emergency

hospital, in the United States hotel block on Beach street, but that

building also caught fire, adding to the scene of horror. The board of

aldermen was summoned to meet at the City hall to take such action as

might be necessary

…

Lincoln street, where the fire broke out

yesterday, is lined on both sides of the street with new and elegant

"fire proof" office buildings [they had stand pipes and water hoses on

each floor]. Lincoln Street begins in Cottage Green, a

square caused by the junction of Summer, Bedford and Devonshire streets,

and extends to Kneeland street and is crossed by Essex and Beach

streets. East, west and north of this section lies the most thickly

settled tenement section of the city.

The locality has long been a terror to respectable wayfarers after

sundown and many crimes have been committed within its borders.

...

The scenes witnessed about the burned district after the excitement had

partially died away were indeed sad ones to behold, and many a cheek

was bathed with tears as the mothers, brothers and sisters of missing

ones walked about wringing their hands and weeping while looking for

some trace of loved ones who had been burned to a crisp or crushed to

death beneath the falling walls of the burned structures. It was the

most touching spectacle witnessed here on any occasion.

Up to an early hour this morning only four of the bodies of those who

lost their lies as a result of the fire had been recovered from the

ruins for the burned buildings. The terrific heat makes the search for

the unfortunates slow and perilous.

...

The total loss sustained by the fire is figured out to be in the neighborhood of $5,400,000. On this amount there is insurance of $3,000,000, held principally by eastern companies. A company in Milwaukee and another in Chicago held several of the larger risks.

Over 200 men are at work to-day clearing away the debris and search for the remains of those cremated in the seething furnace."