|

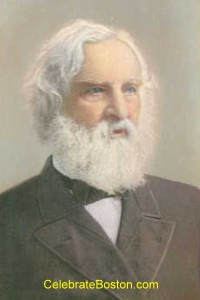

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

1807-1882

"It has fallen to the lot of some American poets to be more admired than Longfellow, to some, perhaps, to be more praised, but to none to be better loved. His lyrics have found their way to homes and hearts the world over. Men, women, and children read his poetry because it tells, in simple, direct fashion, the story of the common experiences of life. It is a pleasure to remember that the man lived what the poet sang, that his courtesy and gentle dignity were the habits of a lifetime, and that his own scholarly attainments never made him exacting toward others.

Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, 'in an old, square, wooden house upon the edge of the sea.' His mother was a descendant of the John Alden whose wooing he celebrated; his father's family came from Hampshire, England. He went to Bowdoin College, where, in the later years of his course, a few poems testify to his love of nature and of legend. He was a classmate of Nathaniel Hawthorne, George B. Cheever, and J. S. C. Abbott. Like most of the literary men of his time, he intended to be a lawyer; but the offer of the professorship of modern languages in his college, determined him to go abroad and fit himself for the work. His stay covered two years.

From 1829 to 1835, when he was chosen to succeed Mr. Ticknor at Harvard, Longfellow lectured to Bowdoin students and wrote for the North American Review. Allen & Ticknor, in 1833, published his first book, containing an essay on the Moral and Devotional Poetry of Spain, and some translations of Lope de Vega's sonnets. Before entering on his duties at Harvard, Longfellow paid another visit to Europe, lingering in Switzerland and Scandinavia. The beneficial effect of European culture at this period of the poet's development has been questioned; and indeed, if Outre-Mer (1835) and Hyperion (1839) had been its only outcome, the public would have reason for regret that he ever left his native shores. These two books, although they were once very popular, mark a time when he exchanged sentiment for sentimentality, and accepted mannerism for style. But the Voices of the Night, also published in 1839, contains some of the very best of his less pretentious work—poems whose simple truth and natural expression. render them popular—The Reaper and the Flowers, Woods in Winter, and The Psalm of Life. The small volume of Ballads, and other Poems, appeared in 1841. The poet's return from Europe, in 1842, was marked by the Poems on Slavery, dedicated to Channing. About this time Longfellow gave a series of lectures on Dante, illustrating them by translations from the work of the great Italian poet.

By the end of the year 1846, he had published the Spanish Student, a collection of translations called The Poets of Europe, and The Belfry of Bruges. The next year is marked by the appearance of Evangeline, the poet's favorite of all his works, and the one perhaps that is most dear to the public, although even it could not succeed in the mission of naturalizing the hexameter among us. The subject was one suggested to Hawthorne by a friend, but he rejected it as unfit for a story, and handed it over to Longfellow, who saw its possibilities. Kavanagh, a novel of little power, and a volume of poems called The Seaside and the Fireside, were published in 1849; The Golden Legend, a drama, in 1851. Hiawatha (1855) raised a storm of enthusiasm and literary controversy as to the cause of its success and its probable permanence. Longfellow called the poem 'An Indian Edda;' the scene was among the Ojibways, near Lake Superior; the meter is rhymeless trochaic tetrameter. Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes has given an ingenious explanation of the popularity of this meter on physiological sounds. The European critics attribute its success to the fact of its being modified from the common Finnish measure. The Courtship of Miles Standish was another successful essay in hexameter, followed by The Tales of a Wayside Inn a collection of poems on various subjects; The New England Tragedies, The Divine Tragedy, and The Hanging the Crane (1874).

Mr. Longfellow had resigned his professorship in 1854. He continued his residence in the 'Craigie House,' famous as the headquarters of Washington in Cambridge [Massachusetts]. There he was, as he says, 'too happy,' and there, in 1861, the tragedy of his life occurred. His wife's dress caught fire as she sat among her children, and she was burned to death. The translation of the Divine Comedy of Dante (1867) was the poet's refuge in his sorrow. It is extremely literal, and has been both praised and blamed on that account. The closing years of Longfellow's life were rich in friendship and success, but there is an increasing seriousness in all his work. The poem, Morituri Salutamus, which he read. at the fiftieth anniversary of his graduation at Bowdoin, is weighty with feeling. In 1880 came Ultima Thule; in 1881 a sonnet on the death of President Garfield. Hermes Trismegistus was his last poem. He died in 1882, and was buried near the 'three friends'?Charles Sumner, Louis Agassiz, and Cornelius Felton—whom he had loved so dearly and mourned so sincerely. England has honored his genius by giving his bust a place in Westminster Abbey."

— English & American Literature, Shaw & Backus, p.429